Spanning the Globe IX

- ANATOMY IN CLAY® System

- Aug 4, 2020

- 3 min read

Lest you think the pandemic is taking forever to run its course, we’d like to bring you some time-related perspective on some anatomy developments around the world. Thanks in large part to developing technologies and curious people, we are learning more and more on our anatomical ancestors.

Let’s start with new research on 400 million year-old fish. An international group of scientists has been studying the acanthothoracids, an early fish group related to the very first jawed vertebrates. The study team has focused on their teeth. Way back then, acanthothoracids added new teeth on the inside of their mouths and inside of more mature teeth, which were located right at the jaw margin inside the lips. In this way, they resembled sharks, bony fish, and early land animals. Humans are somewhat similar, but our “new” teeth sprout from below instead of inside the initial teeth.

These findings were made possible by new, sophisticated equipment at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, (ESRF), in Grenoble, France. Using new technology, the group was able to study the rare fossils without removing them from the rock in which they were found.

Says Per Ahlberg, co-author of this collaborative study, published this year. “When you grin at the bathroom mirror in the morning, the teeth that grin back at you can trace their origins right back to the first jawed vertebrates."

Learn more here,

Next, consider new research on a dinosaur from approximately 183 million years ago:

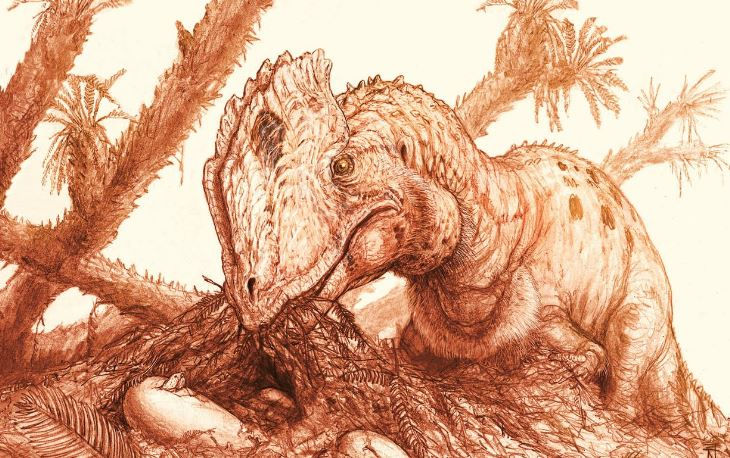

The Dilophosaurus is a large, double-crested carnivore originally excavated near Tuba City, on the Navajo Nation in Arizona. It was originally thought to have a relatively weak jaw and perhaps a venom sac.

But thanks to doctoral student, Adam Marsh, we now know that the creature (which has been roughly depicted and embellished as a dinosaur in Jurassic Park) had, in fact, quite powerful jaws. It was a streamlined creature with a long tail, long legs, and long jaw.

Learn more here from this excellent article in Texas Monthly.

Zoom ahead to just 5.6 million years ago to learn about early human footprints in a place you wouldn’t expect: Europe.

That’s what Polish paleontologist, Gerhard Gierlinski, discovered while vacationing on the island of Crete in 2002. Since then, Gierlinkski has asked colleagues to weigh in on the humanoid foot fossils. That group included the previously mentioned Per Ahlberg, Madelaine Böhme and a group of scientists in Bulgaria and Canada, who have been working on the scarce and fragmentary body fossil record of European Miocene hominins.

The paper they published here disrupted the widely held belief that the first humans evolved in Africa some 3.66 million years ago. The footfall discovery would place humans (homo erectus, related to the relatively younger homo sapiens) on the planet millions of years prior to those humanoids in Africa.

You can imagine the researchers were bombarded with naysayers. “It was six and a half years of sort of a living hell," said Dr. Ahlberg.

Last year, the group convened in Crete to videotape material for a documentary on the new evidence for the early presence of hominins in Europe.

As with the discoveries around the acanthothoracids, new scientific techniques—a palaeomagnetic dating and detrital zircon dating—have led the researchers to these fresh discoveries.

Meanwhile, scientists have crafted a three-dimensional digital skeleton of the “Turkana boy,” another homo erectus specimen dated to 1.5 million years ago.

Using newly developed imaging techniques, the Turkana boy reveals a wider, deeper, shorter ribcage than homo sapiens. Its stockiness is thought to be more related to Neanderthals, which existed after homo erectus but may have bred with the earlier humanoid.

Final thought? Time is a relative thing.

.

.

.

.

.

#ANATOMYINCLAY #spanningtheglobe #400millionyears #turkanaboy #homosapiens #neanderthals #palentologist #Dilophosaurus #jurassickpark #africa #millionyears #hominins

Comments